We welcome a guest post today from Rebecca Ingram, author of the new book Women’s Work: How Culinary Cultures Shaped Modern Spain.

How much extra cooking did y’all do during the pandemic? Did you feed yourselves and household members three meals a day or experiment with sourdough and banana bread to escape from uncertainty during those early pandemic months? How many of those who identify as women have seen the amount of time they devote to carework (care for children, elders, partners, community members) take over their lives in these past pandemic years? How many of you have felt overwhelmed, desperate even, and angry to see studies come out that document the impact this has on women’s professional lives, but have felt little shift in terms of economic and political recognition of that carework?

We know now that this is very much a political issue; it has stakes for how folks who identify as women negotiate their family responsibilities, their outside-the-home work, and their identities as political actors. The dominant paradigm in Spain 100 years ago, however, was that cooking—women’s foodwork—was relevant only to the traditional domestic space of the home and that it had little to do with women as political and economic actors and shifting roles for them as Spain grappled with modernization. Women’s Work challenges that perspective to show how discussions of women’s foodwork were very much part of the ways that Spain was modernizing—in how women were understood and how they understood their own work both in and outside the home.

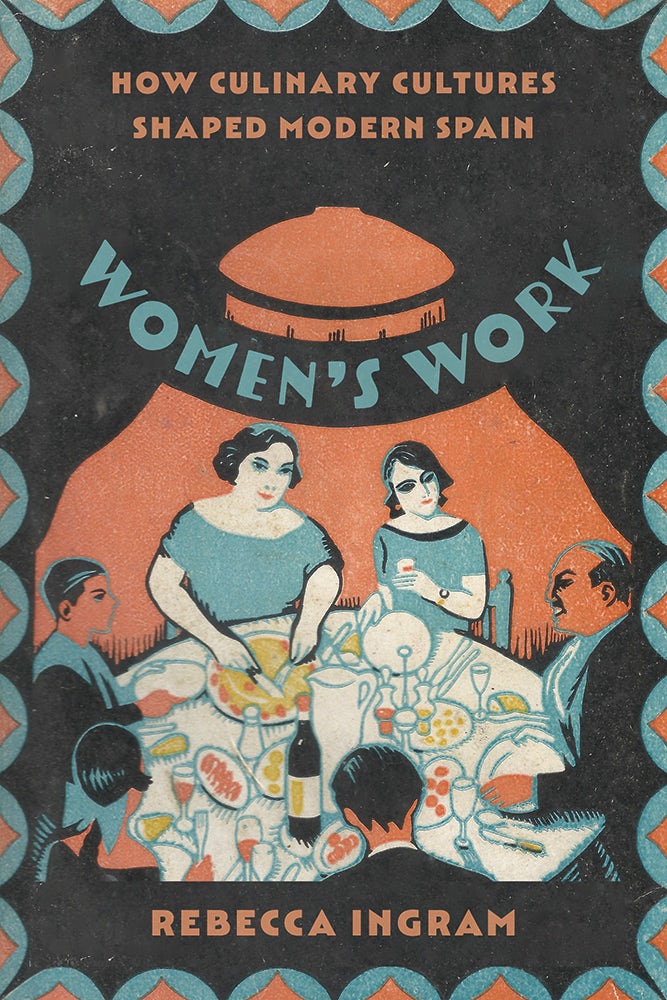

Culinary writing in Spain is a topic I’ve thought deeply about for years, and I’m delighted that this work is becoming available to diverse readers through Vanderbilt. One of the things I enjoyed most about completing its final steps were the images that contacts in Spain generously made available to me to share. In Chapter One, you’ll see a compelling advertisement for olive oil featuring Spain’s best-known feminist writer from the period, Emilia Pardo Bazán (pictured, left*). She was a countess, a renowned intellectual, and she was also acutely concerned about Spanish food and the Spanish nation. How often do we see powerful intellectuals allowing their image to be circulated to sell something quotidian like olive oil? This kind of celebrity was not unusual for male chefs in this period, but it was unusual for someone like Pardo Bazán, despite her interest in cooking. The cover of Women’s Work is an adaptation of one from a cookbook produced by Carmen de Burgos, the focus of Chapter Two. Burgos’s books were what scholars call “kiosk literature.” They were inexpensive and popular, and Burgos herself wrote many of her novels and practical manuals (about seduction! and beauty!) for this kind of public. The image itself was part of a series of covers for her books by illustrator “BON,” or Roman Bonet Sintes. Check out Rebecca Bender’s writing about this series of covers here. For Chapter Three I was delighted to include portraits from the grandson of the “priestess” of Basque cuisine, Nicolasa Pradera, whose life and career that chapter discusses. And the images in the final chapter give readers a way to imagine how culinary education worked in the early twentieth century. Classes were taught in a stadium-style auditorium at the Barcelona-based Institut de Cultura and Biblioteca Popular de la Dona. It’s striking to see the juxtaposition of authority between the male professor in the center (Josep Rondissoni, most likely) and the women in his audience, all of whom knew plenty about cooking already but still sought education about the topic.

Women’s Work is oriented by a feminist food studies approach. In each chapter I delve into how gender ideologies and social class intersected during a period when women and the working class were considered a “problem” to be solved for Spain to achieve modernity. The study of food involves taking into account the bodies and subjectivities of people who produce food—how it’s processed, prepared, and written about. These are all things that also tell us about power. Which groups of people use their bodies to produce what we eat? Which groups decide what meanings specific foods acquire? These questions were relevant to Spain 100 years ago and remain central to understanding its diverse and multi-faceted food cultures today.

*Advertisement for MO olive oil, featuring Emilia Pardo Bazán, that appeared in the magazine Caras y Caretas de Buenos Aires (after 1890). Image provided by the Arquivo of the Real Academia Galega (RAG) and the Casa-Museo de Emilia Pardo Bazán.

New Series Announcement: Global Black Writers in Translation

New Series Announcement: Global Black Writers in Translation